What Should the Voting Age Be?

Dana Kay Nelkin

University of California, San Diego

Abstract

In this paper, I endorse the idea that age is a defensible criterion for eligibility to vote, where age is itself a proxy for having a broad set of cognitive and motivational capacities. Given the current (and defeasible) state of developmental research, I suggest that the age of 16 is a good proxy for such capacities. In defending this thesis, I consider alternative and narrower capacity conditions while drawing on insights from a parallel debate about capacities and age requirements in the criminal law. I also argue that the expansive capacity condition I adopt satisfies a number of powerful and complementary rationales for voting eligibility, and conclude by addressing challenging arguments that, on the one hand, capacity should not underly voting eligibility in the first place, and, on the other, that capacity should do so directly and not via any sort of proxy, including age.

1. Introduction

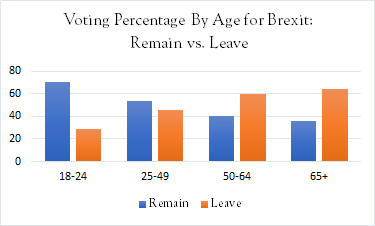

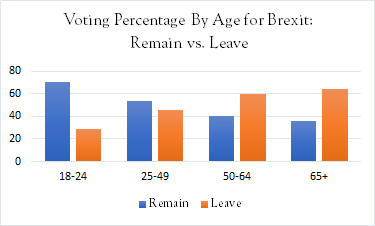

We are in a moment when the once-ingrained assumption that the voting age should be 18 years old (or higher) is being questioned. In fact, the voting age has already been lowered in some places and we have a growing body of empirical data about the effects of this change. For example, the voting age was lowered to 16 years of age in Austria in 2007 for most purposes, in Scotland in 2015, and in some cities in the United States for participation in local elections. A bill proposing lowering the voting age has very recently been proposed in Australia, and there is now a lively debate in many other places. Lowering the voting age has important potential implications on a number of fronts, including for the particular consequences of elections and referenda, for the rights of citizens, and for the aims of democracy itself, all to be explored in what follows. One particularly dramatic example of the effect on outcomes is illustrated by comparing the outcome of the United Kingdom referendum on leaving the European Union in 2016 with what the outcome might have been had 16- and 17-year-olds been eligible to vote. Although in Scotland the voting age had been lowered a year earlier, only those 18 and over in Scotland and elsewhere in the United Kingdom were eligible to vote on the referendum. Given the overwhelming support for remaining in the EU among those 18-24, it is reasonable to conclude that 16- and 17-year-olds would also have backed remaining by a large margin, and possibly by sufficient numbers to have changed the outcome.

Source: YouGov (https://yougov.co.uk/topics/politics/articles-reports/2016/06/27/how-britain-voted)

As many have noted and as may seem to go without saying, there is a presumption that citizens in a democracy have the right to vote, unless that presumption is defeated. The question to be addressed in this paper is whether that presumption is indeed defeated for the group whose members are under 18 years of age. Why should there be such a presumption? There are a number of complementary answers. First, as Jeremy Waldron (1993) puts it, on an Aristotelian model, “participation in the public realm is a necessary part of a fulfilling human life” (p. 37). Call this the “good life” rationale. Second, on an “interests-protection” rationale, participation is a form of self-protection and a way to give voice to one’s interests. Third, as autonomous agents with the capacity for valuing and for self-governance, people have the right to provide input in the creation of whatever laws constrain them. Christopher Bennett (2016) applies this idea to another way of expanding the franchise, namely, the inclusion of felons, but it could just as aptly be applied to expanding the franchise to those younger than 18:

[P]erhaps most fundamentally, having the right to vote is also a marker of an important status, shared equally with other fellow citizens: it marks a person as having the ability and right to govern her own life and to join with others in determining the government of the collective.

In a democracy, then, the legal right to vote is a marker of one’s status as an equal with the capacity for autonomous choice in decision-making for the collective, and one’s exercise of the right is an expression of that fundamental capacity. Insofar as we have a right to be treated as equals in this way, rather than having some make decisions for others, the legal right to vote rests on this more fundamental right. Call this the “autonomy rationale”. On the basis of these rationales alone, because of the importance of the right to vote, it seems that the presumption should be that citizens should have such a legal right unless reasons can be provided that they should not. Applying this point to the question of voting age, Tommy Peto (2017) writes that

“[t]herefore, there should be a presumption in favour of lowering the voting age, unless someone can identify a normatively relevant difference between adults and adolescents to rebut that presumption” (p. 3).

Before turning to the question of whether such a presumption is in fact rebutted in the case of 16- and 17-year-olds (and perhaps those even younger), it is worth noting some additional rationales for lowering the voting age. As the Brexit vote illustrates, it can happen that those of different ages have different perspectives on an issue, while all having something at stake. And arguably, the quality of public deliberation rises when more people contribute to the public debate and ultimately to decision-making. As Lisa Hill argues in the context of defending compulsory voting as a means of raising voter turnout, low turnout perpetuates “elite dominance, social inequality, and unrepresentativeness. It therefore impedes the ability of democratic governments to do what they are supposed to do: to be ‘of the people, by the people, and for the people’.” Further, she points out that low turnout also means that the legitimacy of democracy is undermined because it is biased as a result of the fact that certain marginalized members’ voices are not heard. This last point is a contingent one, since it is possible to imagine a society in which interests are quite homogeneous. But just because it is contingent does not make it unsystematic or unimportant. And though the point here is made in favor of compulsory voting, it equally supports lowering the voting age insofar as those under 18 have particular interests that are otherwise unrepresented directly in elections. Thus, there are further arguments for a presumption of including as many citizens as we can in the voting population. Some of these arguments concern better overall outcomes judged on a variety of criteria including higher quality as a result of a better public debate, others concern the very aims of just democratic institutions, and some concern both, such as the idea that outcomes are better when the results yield more equality and representativeness. So, in addition to the rationales that all focus on the importance of voting for individual prospective voters, namely autonomy, good life, and interests-protection, we have what I call “outcome” and “aim of democracy” rationales.

Fortunately, there is no need to choose among these various reasons for a presumption in favour of lowering the voting age. But I will return to them later, because which reasons we recognize can, in principle, lead to different recommendations about what, if any, the minimum voting age should be, as well as different verdicts on just what the criteria for voting rights should be. I will argue that, in the end, even the ones that would seem to yield the most demanding criteria for voting rights still lead to support for lowering the voting age.

Now, attempts to dislodge the presumption in favor of lowering the voting age very often appeal to differential capacities between those under and those over 18, together with the claim that these capacities have normative significance. But recently these arguments have been turned on their heads by those arguing in favor of lowering the voting age. This will be the starting point for my assessment of the debate in what follows. The plan of the rest of the paper is as follows. I begin in sections 2 and 3 by considering arguments that appeal to particular capacities in their defense of lowering the voting age, based on the ideas that age is a proxy for such capacities, and that opponents’ arguments have made a mistake about the age at which relevant capacities develop. While I believe that both of these arguments have much to recommend them, I show in section 4 that they are both missing an important part of the picture that adds a potential obstacle in the path to the conclusion that the voting age should be lowered. In section 5, I show how that obstacle might be overcome, explaining how, though the original conclusion is correct, the reasoning—including the marshalling of relevant empirical evidence—must be different. All of these arguments for expanding the voting population ultimately rest on two underlying assumptions. First, they assume that age is an appropriate proxy for the relevant capacities, and second, they assume that capacities ought to be the fundamental criterion for voting age in the first place. In sections 6 and 7, I defend both of these foundational assumptions from important challenges.

2. Political Maturity and Cognitive and Moral Development Arguments

An influential argument for retaining the voting age of 18 in those jurisdictions that have it relies on an appeal to “political maturity”. The idea is that voting eligibility should depend on political maturity, which is in turn understood as encompassing political knowledge, stability in preferences, and interest in political life. Advocates of this argument, such as Chan and Clayton (2008), offer evidence that 16- and 17-year-olds fall well behind those 18 and older along each of the three measures.

But others have turned the argument on its head, arguing that in fact there is evidence that 16- and 17-year-olds do just as well on these dimensions—or, at the least, that when the vote is made available to them, they catch up to their older peers. And it is not surprising, on reflection, that if one lacks an opportunity in a given domain, one will have less knowledge and interest in it than if one has an opportunity to exercise choice in it. Peto, for example, citing the example of Austria, points out that the very act of making the opportunity available is likely to increase interest as well as knowledge. Notably, it is also the case that political participation among the youngest voters in the United States has soared, as they are disproportionately affected by certain phenomena ripe for legislation and policy change, such as climate change and gun control. Voting rates among 18-29 year-olds in midterm congressional elections in the United States increased by 79% between 2014 and 2018, and expanded opportunities for pre-registration by 16- and 17-year-olds in the state of California, among others, have been seized by hundreds of thousands of teens.

But perhaps political maturity is not the entire story of capacity or qualities relevant to voting rights. It also seems important that 16- and 17-year-olds have reached a stage of reasoning ability that is comparable to that of adults. As Peto (2017) writes, citing Steinberg, there is “no significant difference in cognitive abilities of 16-year-olds and adults,” and 16-year-olds have reached the same level of moral reasoning, logical reasoning abilities, and scientific/means-ends reasoning. Peto concludes that as a result they, too, possess “moral autonomy”. Along related lines, there is good reason to believe that 16- and 17-year-olds also have the capacity to value the act of voting itself, a capacity that some have also thought is required for full voting rights.

While I believe that these arguments successfully rebut particular challenges to lowering the voting age and contain much insight, it remains an open question whether they have fully captured all of the capacities relevant to voting rights. Of course, armed with the presumption in favor of voting rights for those younger than 18, it is enough to rebut challenges to the presumption, and that is the explicit aim of these authors. But it would be welcome if we could offer a comprehensive account of just what capacities are relevant to the voting age. If we can do this, then it will also be possible in theory to make the case that no further attempts of this kind to challenge the presumption simply can be successful.

Before turning to that task, it will be helpful to examine a different kind of argument focused on capacity in support of lowering the voting age.

3. The Comparative Argument: Eligibility for Criminal Liability and Political Participation

Nicholas Munn (2012) begins with the kind of presumption in favor of extending voting rights with which we started, and agrees with many others on both sides of the debate that the most promising way to rebut the presumption is by pointing to some capacity that is lacking in 16- and 17-year-olds. As he writes: “[T]he right of political participation, through voting, is enshrined in human rights instruments. As such, paternalistic defenses of exclusion cannot succeed, and the justifiability of the threshold must rest on some other ground. The most promising ground for exclusion, and the one critiqued here, is incapacity.” He argues, however, that if the opponents’ claim is that 16- and 17-year-olds are generally lacking in a relevant capacity, they face a challenge of inconsistency. For when it comes to criminal liability, the minimum age is considerably lower than 18 in many jurisdictions, including the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia. Taking Australia as a case study, Munn points out that one can be criminally liable at age 14, and that if the prosecution makes a positive case that one has the relevant capacities at an even earlier age, then one as young as 10 could be criminally liable. So, much hinges on just what the relevant capacities are for both criminal liability and voting.

Munn presents the capacities for criminal responsibility, as embodied in the Australian doctrine of doli incapax: “[C]riminal responsibility may be attributed to members of this group [10-14 year-olds] when it can be shown that they were aware in undertaking the actions concerned that what they did was …wrong, subject to criminal sanction.” This is a significant requirement on understanding, and it is assumed to be met by those older than 14. While the default presumption is that it is not met by those younger than 14, this is treated as a rebuttable presumption.

This test for criminal responsibility presupposes a capacity to understand that one’s actions are wrong and subject to criminal sanction, and it contrasts with tests for voting capacity. Now, there are few such tests in existence in the countries Munn focuses on, and they are rarely administered. But one such test is the Doe test, put forward in a federal district court decision in Maine, to determine whether those with dementia or other severe mental impairments should be eligible to vote. According to that test, “[i]t is only if people lack the capacity to understand the nature and effect of voting such that they cannot make an individual choice” that they are disqualified. As Munn argues, the capacity required for voting—at least as embodied in one of the few tests to be found—is no harder to achieve than is passing the test for criminal liability. So, the respective age thresholds for criminal liability and voting cannot be justified.

Of course, one might respond to this challenge in a variety of ways, including by raising the age for criminal liability and the voting age. But Munn encourages us in the view that the voting age should be lowered as well, on the grounds that those as young as 14 typically have the capacity in question. This is an important argument, and the idea that we ought to achieve consistency, and to do so while ensuring that each age threshold is set correctly for the right reasons, is hard to dispute. At the same time, I believe that the argument points the way to our being able to do even more, namely, offer a fuller account of the capacities that matter for both criminal liability and voting age, and I take this up in the next section.

4. A Challenge: Raising the Bar to a More Expansive Capacity Condition

The arguments set out above focus largely on cognitive capacities. If cognitive capacities are the only capacities that are relevant to a right to vote, then they will have provided strong support for the conclusion that we should lower the voting age. Now the question arises: are these the only capacities that are relevant to eligibility to vote? In this section, I make the case that they are not, and argue in favor of expanding the set to include volitional and motivational capacities, as well. If this is correct and additional capacities are required, then, at the least, more work will need to be done in order to defend the idea that those under 18 are on a par with those over 18 when it comes to the relevant capacities.

Just as the case of criminal justice was illuminating in providing the comparative argument discussed above, it is instructive here, as well. As we will see, in both domains, we find two options: a “narrow” view that takes only cognitive capacities to be relevant and an “expansive” view that includes volitional ones. As we will see, the criminal justice domain serves not only as a good analogy, but also as a guide to identifying relevant capacities when it comes to voting.

Here it is most helpful to begin by focusing on the capacity captured in the so-called “insanity defense”. Although this defense is technically limited to a small subset of criminal excuses, I will show how it can be thought of as a template for a completely general incapacity excuse. On one model of the insanity defense, we have a defense that implicates only a narrow set of capacities, namely knowledge of one’s actions, and of their wrongness. The M’Naghten Rule captures this idea:

M’Naghten Rule: A defendant is excused by reason of insanity if the defense proves “at the time of committing the act, the accused was laboring under such a defect of reason, from disease of the mind, as not to know the nature and quality of the act he was doing or, if he did know it, that he did not know what he was doing was wrong.”

This test offers a parallel to the Australian test discussed in the previous section for rebutting the assumption that those younger than 14 lack criminal liability. It identifies a capacity of understanding, or in other words, a cognitive capacity of a particular kind as required for liability.

A second model is more expansive and includes not only cognitive but also volitional capacities. An example of this model is captured by the Model Penal Code, an ideal set of statutes commissioned by the American Bar Association and intended to guide states as they modify and enact new legislation.

Model Penal Code: “A person is not responsible for criminal conduct if at the time of such conduct as the result of a mental disease or defect he lacks substantial capacity either to appreciate the criminality [wrongfulness] of his conduct or to conform his conduct to the requirements of law.” (1981/2002, italics added)

Now the two models differ along multiple dimensions, but, for our purposes, one is especially important. The Model Penal Code (MPC) introduces an additional way of being excused from criminal responsibility; or, to put it another way, it requires an additional capacity in order to be criminally liable. In particular, one must have not only a cognitive capacity of some sort to recognize the wrongfulness of one’s actions, but one must also have a volitional capacity to act on the reasons one recognizes for avoiding wrongdoing. On the MPC test, one might then fail to be criminally liable in two different ways. On the one hand, one might lack a cognitive capacity, whether ultimately dependent on lacking an ability to reason well or to understand moral concepts or their application or on something else. On the other, one might lack a volitional capacity, or have one sufficiently impaired that it is not “substantial”, for example, by being subject to compulsive desires or impulses. As is apparent, this difference between the two tests by itself yields quite different verdicts, with the M’Naghten Rule excluding people with only a volitional incapacity such as Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder from the defense, and the MPC including such people (given that the volitional capacity is sufficiently impaired).

If we think that ultimately what is required for liability is the ability to respond to, and not just recognize, reasons for avoiding wrongdoing, then we should accept this additional capacity as a requirement for liability. As I have argued elsewhere, along with many others, this additional capacity seems essential for assigning both moral and legal responsibility. Further, there is reason to think that this sort of test ought to be generalized beyond the context of legal insanity. If we were to drop the requirement of defect or disease, we would simply have a test for capacity that can help us answer many questions about who should be criminally liable, including about the status of youth. Ultimately, it seems that capacity itself is what ultimately matters for liability and its flip side, excuse. One might then use this sort of test to unify our approach to a number of different excuses in the law.

Now return to the question of age thresholds for criminal liability. Accepting this further requirement on liability serves to raise the bar, and, with it, the age threshold for criminal liability. For volitional capacities develop gradually, and arguably continue to develop even after cognitive reasoning capacities are in place. For example, those who are younger gradually develop capacities for impulse control, and have less capacity to resist peer pressure than those who are older. As Steinberg et al (2009) point out, in contrast to the literature supporting parity in cognitive and moral reasoning capacity between 16-year-olds and adults, “the literature on age differences in psychosocial characteristics such as impulsivity, sensation seeking, future orientation, and susceptibility to peer pressure shows continued development well beyond middle adolescence and even into young adulthood.”

The question I want to pose here is whether we should accept a similar expansion of the kinds of capacities relevant for voting rights. In at least many discussions of capacity relevant to voting, the focus is entirely on cognitive capacity, and so we find in them a parallel to the first model of narrow capacity in the criminal domain. In fact, there is more than a parallel here, as I will argue. Of course, there is a difference in that in the criminal domain the focus is on understanding what one is doing and understanding right and wrong, whereas in the voting domain the focus is on understanding the process and point of voting and of the issues at stake in elections. Nevertheless, in both cases, the capacities in question are broadly ones of reasons-responsiveness. In other words, in both cases, the capacities in question include the capacity to understand the world accurately and to understand what values are at stake in decision-making. But now unless we consider the possibility that volitional capacity is also required, it is open to opponents of lowering the voting age to rebut the presumption in favor of a broader electorate by appeal to clear, albeit gradual, differences that typically occur between young people in different age groups. An opponent of lowering the voting age might object that while many of those younger than 18 are on par with those older than 18 when it comes to cognitive capacity, as a group they are notably less developed on a whole host of measures of volitional and motivational capacity, such as impulse control, susceptibility to peer pressure, and more. Thus, more generally, their volitional capacity to turn their cognitive judgments about what it is best to do into actions that truly reflect those “best judgments” is underdeveloped in a way relevant to setting the voting age. Opponents of lowering the voting age might reasonably ask: what good is it to be able to make good judgments if one lacks the reliable ability to vote accordingly?

This challenge rests on two key premises:

(1) The voting age (if any) should be determined by whether individuals in various age groups have both cognitive and volitional capacities relevant to voting to a sufficient degree of development.

(2) Those under 18 typically do not have the relevant volitional capacities to a sufficiently well-developed degree.

I believe that the best response to this challenge is to question premise (2), since premise (1) is true and important. To see why (1) is true, consider that at least some of the foundational reasons that provide support for the presumption in favor of lowering the voting age also support thinking of relevant capacity more expansively.

Consider first the autonomy rationale, the idea that the right to vote is simply a manifestation of one’s status as an equal with the capacity for autonomous choice in decision-making for the collective, and that one’s exercise of the right is an expression of that fundamental capacity. Of course, there are different conceptions of autonomy, but I believe that the ones most relevant to our question are united in taking volitional capacity to be essential to autonomous agency. I favor a substantive conception of autonomy, according to which autonomous agents are ones who are capable of responding to the reasons that there are. On this conception of autonomy, sufficiently well-developed capacities of both kinds are relevant, since responsiveness to reasons is a function of both recognizing and being able to act on such reasons. But not everyone accepts this conception of autonomy, for this or any other purpose. On a different conception of autonomy, agents are autonomous when they have the capacity to govern their actions according to the reasons they themselves endorse, whether right or wrong. On this conception of autonomy, one must also have both sufficiently well-developed cognitive and volitional capacities, insofar as one must be able to bring one’s actions into harmony with the motivations that one endorses. Though it is an important question which of these (or some other) conceptions fits best with the reasons in favor of a presumption of voting rights, I believe that it is possible to set it aside for current purposes. For we can note that a wide variety of conceptions of autonomy require volitional capacities, including any that include a capacity to be motivated on the basis of what we take to be reasons or to be desirable. If any one of these conceptions captures the appealing idea that the right to vote is an important marker of this status, then we will have reason to include these capacities as part of what it is to be an autonomous agent. And in that case, insofar as we take voting to be a right for autonomous agents, our criteria for eligibility should include volitional as well as cognitive capacities.

I believe a similar line of reasoning also works for other rationales for the importance of voting, such as outcome-focussed rationales. For these, too, also point to a substantial volitional capacity requirement. For example, when we focus on the quality of outcomes, say, ones that provide greater representativeness of the electorate, it is crucial that voters have the capacity to put their best judgments into action. It would not be enough to recognize reasons one has; one would need to be able to translate those into action when one votes in order to have the relevant sort of impact on the outcome of an election. Now it is possible that this sort of reasoning might not apply to all possible reasons for thinking voting important, and that there should be a presumption in favor of voting. For example, if the goal is to improve the quality of public debate, one might think that what is essential are simply more contributions to the marketplace of ideas prior to voting. But even here, volitional capacities are required to enter the public debate, and it seems that ideas will be taken more seriously if they come with the prospect of being supported in concrete ways such as votes. Many 16- and 17-year-olds campaigned to remain in the EU, for example, and while their voices might have been heard, one might argue that if they had actually brought their prospective votes to bear on the discussion, their voices might have had even more impact.

Thus, at least several central rationales for the importance of voting that support the presumption in favor of lowering the voting age point to a requirement of both cognitive and volitional capacity. And yet, as we have seen, this very point also makes the presumption vulnerable to a challenge from the body of research that shows significant typical development of such capacities over the time period between 16 and 18.

We cannot answer challenges to lowering the voting age by simply pointing to rough parity of 16-year-olds with adults on political maturity (understood as a combination of knowledge, stability of preference, and interest) or cognitive powers or moral reasoning capacity. For as we saw when it comes to criminal liability, unlike these other qualities and capacities, there is a large body of research casting doubt on parity when it comes to volitional capacity in particular. (In other words, we face the challenge of rebutting premise (2), as well.)

Before addressing this objection head-on, it is important to note that how good or how well-developed one’s capacities are is a matter of degree. What is needed is that they pass a relevant threshold, or at least that they pass a relevant threshold for the quality of capacity that is needed in the relevant circumstances. I will return to this point in section 6. For now, it is simply important to note that if autonomous agency is to be understood in terms of capacities and their exercise, and capacities come in degrees, then autonomous agency itself comes in degrees. I know of no algorithm to determine relevant thresholds, and will rely in what follows on an intuitive understanding of when capacities are well-developed enough, as well as on comparative assessments of capacities of those under 18 and those over 18.

With this in mind, we can turn to the question at hand. Are those under 18 lacking in volitional capacities that are relevant to voting in comparison to those over 18, and to an extent that justifies withholding the right to vote for 16- and 17-year-olds?

5. Clearing the Bar: Showing that 16- and 17-Year-Olds Typically Satisfy Even the Expansive Capacity Condition for Voting

Whether those younger than 18 have parity with those over 18 on a more expansive set of capacities is in large part an empirical question. While a complete survey of the relevant psychological literature would require more than I can provide here, I offer what I take to be strong reasons for thinking that, though there are differences, the differences do not undermine parity in the quality of capacities where it matters for voting. My strategy is to consider some main ways in which volitional capacities appear to be less developed in younger teens, and to show that none of them constitutes impairment in ways that matter for exercising the right to vote.

First, consider vulnerability to peer pressure. There is good evidence that peer pressure has the greatest influence between the ages of 14 and 18. And this might be precisely the kind of vulnerability that reduces capacity to do what one takes to be supported by the reasons, or to be motivated by what one values or desires to be moved by. But there are reasons to think that this is not ultimately a problem for lowering the voting age. The first is that there is also good evidence that the influence of peer pressure varies significantly by domain. While peer pressure may be strong in the domain of, say, drug use, especially under circumstances in which the alternatives would be costly, it may not be strong in other areas such as family involvement. It is notable that voting is typically done in private, and failure to bend to peer pressure does not have the same obvious costs as other failures.

Next, consider impulse control and sensation-seeking. There is good reason to think that contextual factors matter greatly here as well. Addressing the differences between (many) criminal contexts and contexts of medical decision-making (such as whether to have an abortion), Steinberg et al (2009) write:

When it comes to decisions that permit more deliberative, reasoned decision making, where emotional and social influences on judgment are minimized or can be mitigated, and where there are consultants who can provide objective information about the costs and benefits of alternative courses of action, adolescents are likely to be just as capable of mature decision making as adults, at least by the time they are 16.

There is good reason to think that voting is done in this more deliberative sort of context, rather than in ones more typical of at least many criminal contexts.

To recap: I have argued that in order to forestall further challenges to the presumption that the voting age should be lowered, a more complete account is needed of the capacities that seem to be presupposed by the reasons supporting the presumption. I have suggested that on a more complete account, more empirical considerations must be brought to bear to show that there is indeed parity between 16- and 18-year-olds when it comes to the relevant capacities in the relevant contexts. While I have not been able to do an extensive assessment of the empirical work, I have tried to show that along the dimensions that matter for voting in particular, we have reason to believe that there is parity, even though there are significant differences in capacity between 16- and 18-year-olds that are relevant in other contexts, such as criminal liability.

Given the empirical evidence set out here and in previous sections, if age is a good proxy for capacity, then it seems that 16 is an appropriate one. Before the age of 16, it is less typical that both cognitive and volitional capacities are developed in relevant ways. If, however, we were to learn more that suggests that such capacities typically develop earlier, then the same reasoning would yield a different verdict and recommend that the age requirement be lowered further. In this way, the argument is sensitive to potential new developments in developmental psychology. But I believe this to be a virtue of the account. The account ought to be flexible enough to accommodate possible correction about the empirical facts of human development. For now, the empirical evidence that we have seems to converge on the age of 16 as a defeasible age to serve as a proxy for the relevant capacities.

Even so, more work remains. For there are two assumptions underlying the argument thus far that might be challenged. The first is that age is a legitimate proxy for the capacities relevant to voting. And the second is that capacity is all that matters in either rebutting or defending the presumption that the age should be lowered. I take up these two challenges in the remainder of the paper.

6. Is Age a Legitimate Proxy for Capacity?

One might accept much of the argument thus far, and yet ask why we should not simply appeal directly to the capacities in question in assigning eligibility to vote, rather than to age, which is at best an imperfect proxy. For there are individual differences, so that some people under 16 clearly have the relevant capacities, and some over 18 do not. If capacity is what matters, is there an injustice in using age instead? Should we instead administer a direct test for capacity?

Here is an argument in favor of using age, such as the age of 16, as a proxy. Given that it is imperfect, there will be some false positives: that is, there will be those whom the proxy treats as having the capacity when they do not. And there will also be some false negatives: that is, there will be those whom the proxy treats as lacking the capacity when they have it. For the false positives—those under 18 who gain the legal right when the proxy is changed to 16 but do not possess the capacity—it seems that no injustice has been done; and as for other negative consequences, it is worth noting that it is likely that many who are over 18 also do not possess the relevant capacities (given typical parity), so the situation would not seem to be worse than it currently is in this respect. And there is additional reason for endorsing the status quo of accepting some false positives when it comes to those over 18, capturing why we do not currently have a universal capacity test. The costs of a test, from lack of agreement of how to construct it to the serious risk that it might exclude those it should not exclude, speak against having a test, even at the risk of allowing for an over-inclusive voting population. It is worth the price of some false positives in order to avoid the risk of false negatives. When it comes to a test, some of its false negatives could disproportionately include populations who are already victims of injustice, such as those who have not benefited from the test-taking skills that those who have great access to quality education acquire as a matter of course. And this cost of false negatives would increase still further if we were to administer a universal capacity test. Thus, the costs of a test are potentially quite high, even if it could allow some who are younger than 18 and who have the relevant capacity to vote if they are able to pass it. Thus, when it comes to allowing some false positives by having the age proxy, this seems a price worth paying, as it is for those in older age groups.

The more troubling group affected by the use of the age proxy is that of the false negatives allowed by the age proxy itself—that is, those who have all of the relevant capacities and are excluded on seemingly arbitrary grounds of age, simply because they are younger than 16, say. There does appear to be injustice to them. One response here would be to allow for the age restriction to be “rebuttable”, in a way analogous to the age threshold for criminal liability in some jurisdictions. In this way, age would remain as a proxy, but there could be a means of overriding the default minimum age. Of course, this would introduce some of the same concerns about a general test for capacity. What would the criteria be for successful rebuttal? And if we had a good test, why not offer it as a general test to all prospective voters? I think that there could be grounds for restricting the test in question precisely on the grounds that restricting it would reduce the risk of under-inclusion by means of a universal test. But converging on a non-controversial test would still be a tall order.

Is there a defense of the proxy even if it is used in a strict and non-rebuttable way? One approach is to recognize that rights are being infringed, but nevertheless justify the infringement on the grounds that the alternatives are simply too costly and that, in the case of voting in particular, the positive rights that are infringed are infringed only temporarily. Insofar as the infringement is temporary, the case is disanalogous to other candidate criteria, including results on standardized tests, which may continue to yield under-inclusion of the same individuals over time. So, in this way, we might accept the proxy as the least bad option among others, each of which allows for some infringement of some rights. I believe that this line of reasoning is promising, but if it ultimately fails, the idea that age is legitimate as a proxy for capacity that might be rebutted in particular cases is worth developing.

Before continuing, it is important to assess a recent argument that appears to raise a quite general obstacle to using age as a proxy for capacity in the realm of criminal justice. Gideon Yaffe (2018) argues that when it comes to criminal liability age should not be used a proxy, and if his argument succeeds then it appears to transpose to capacities relevant to voting, as well. If it succeeds, then the preceding argument must be rejected after all.

Yaffe’s argument is that using age as a proxy for the capacities relevant to criminal liability has an unacceptable empirical dependence. If we were to receive empirical evidence that altered the age, or that made other or additional markers better proxies, then, by parity of reasoning, we ought to change the age or use other or additional proxies. But our attachment to not altering the age for criminal liability and treating those older than 18 as adults as a matter of course is strong, and we have the strong intuition that those under 18 ought to be treated differently than adults (at least presumptively). Thus, he argues, we must find a different way entirely to justify the age threshold.

In a bit more detail, there are two strands of reasoning here. One is that age is “intuitively sticky” in this case in the sense that if we were suddenly to receive highly credible empirical evidence that something other than age—say, height—or a much younger age—say 12—is a better proxy for the relevant capacity, then we would still “recoil” from switching proxies. But if we recoil, this undermines the idea of using age as a proxy, and suggests that there is some other rationale at work in the first place.

In reply, I believe that this overestimates the stickiness of our commitment to the age of criminal liability being 18. At other times in history, people were perfectly comfortable holding children as young as 7 criminally liable. Presumably, this is because they thought of children differently. As we have learned more, our views about liability have shifted. And our views of when “childhood” ends have evolved quite rapidly in recent decades, as neuroscientific research together with observational studies show that development is not complete at 18 and is in fact far from completion. Much has been printed about parents’ changing relationships with their college-aged children, including a growing trend toward intervening in more ways in their children’s lives, a practice which seems to presuppose parents seeing their children as not yet full adults into their twenties. For these reasons, it is far from clear just how “sticky” our commitment is to the age of 18 for capturing a status associated with criminal liability.

There is, however, a second and more powerful way of developing the argument of empirical dependence. Yaffe has us consider the proposal that it might be more accurate (fewer false positives and false negatives) to have differential ages depending on sex or gender. The age of liability under this more accurate assessment might recognize liability for women at the age of 16 and for men at the age of 18. Even if this were more accurate as a proxy for relevant capacity, we recoil here, too. Or imagine a case in which something else, such as race, were a more accurate predictor. Again, if we recoil at these suggestions, then it seems we must recoil at the idea of using age as a proxy in the first place. Presumably, this is because the point of using the proxy is to track what really matters; if we find a better “tracker”, the same reasoning ought to support using the better tracker.

Now, the defender of using age as a proxy for liability has a reply here. Not all proxies are created equal, not even all equally accurate ones. Accuracy is not the only value. As Yaffe notes, we much prefer false negatives to false positives in the criminal context. Blackstone famously offered us a ratio: better for ten guilty people to go free than for one innocent person to be convicted. We can consistently prefer a system with one proxy that sacrifices something in the way of accuracy in order to minimize false positives relative to a system with a different proxy that preserves it.

Consider again Yaffe’s thought experiment in which race and age together are a more accurate proxy than age alone. Yaffe writes—and I agree—that using such a proxy would be abhorrent. As he speculates, one reason for this reaction might be that because of the history of racial oppression we take the disvalue of false positives using such a race-based system to far outweigh any value in increased true positives, and so the possibility of our actually preferring such a system overall is highly unlikely. As Yaffe writes: “False positives in a race-sensitive system are so damaging that the improvements in true positives would have to be enormous to outweigh them—so enormous that we can be almost certain that any race-sensitive system would be far worse than a race-blind system”. Perhaps this is why we simply cannot imagine preferring such a system over one that is less accurate and does not invoke race. Thus, we do recoil, and we have a compelling explanation, consistently with taking age alone as a proxy for capacity.

So far, so good. But Yaffe responds: the fact that such a system would be unlikely to be preferred, taking disvalue of false positives into account, is not relevant to the argument; the point is that we can imagine a situation in which we would prefer a race-sensitive system and, in that case, the defender of using age as a proxy will have to give the wrong verdict. But I think that this reasoning can be resisted. First, I am simply not sure that we are imagining such a situation even when described to us, or that in the event that we succeed, we still retain the same intuition. We may not be good at eliminating the racism of our current world as we undertake the imaginary task Yaffe asks of us. The world would have to be vastly different than it is, and if we were truly imagining such a different world, it is possible that our intuitions would change. But I think that the defender of the age proxy need not rely on this point. There could be reasons to reject the use of certain proxies that are independent of the disvalue of false positives as compared to false negatives. The use of certain proxies might simply be off-limits. We can accept the use of proxies even when they track but do not by themselves capture that in virtue of which the purpose in question is being served; but when the very use of the proxy would have a harmful and misleading tendency to appear to be that in virtue of which the purpose in question is being served, or when it might run the risk of appearing to be essentially connected with what matters, we should not use it. In other words, if we used race to track capacity when there was only a contingent correlation, it might wrongly appear that race is itself the deciding factor, or that race is necessarily connected with capacity. This appearance would not reflect reality, but appearances by themselves can be extremely damaging. In this case, they could be so damaging as to make the use of such proxies off-limits.

For these reasons, I do not believe the case for rejecting age as a proxy even for criminal liability has been made.

And if this reasoning concerning empirical dependence does not dislodge the reasons in favor of using age as a proxy for criminal liability, it seems to have even less force against using age as a proxy for voting. Intuitions about voting age appear to be even less “sticky” than those for criminal liability. It was not long ago that the voting age in the United States was 21. And it does not seem shocking that jurisdictions like Scotland and Austria would consider lowering it. As for the worry that using age as a proxy for capacity presupposes some principle that would commit us to using an “abhorrent” proxy, as before there is no reason that the advocate of age as a proxy must accept such a commitment.

7. Should Capacity Underly an Age Criterion in the First Place?

There is a final assumption to examine, and that is the idea that it is capacity—and capacity alone—for which age is meant to be a proxy in this picture. Perhaps something other than, or in addition to, capacity justifies the use of a particular minimum voting age. I have offered reasons for thinking that it is capacity that is relevant: given the importance of the right to vote, including that it marks equal status as autonomous beings and that there is much at stake for potential voters at any age, the presumption is in favor of expanding the voting population to include those who are younger and indeed have the equal status in question which is determined by capacity. But it is possible that some other reason for denying the right to vote to members of a certain age group overrides these reasons, and I examine three here.

One reason that perhaps comes first to mind is that the age of emancipation is typically 18, or, more informally, parents have special legal duties toward their children younger than 18 and also legal control over their children younger than 18 that also ends at 18. Closely associated with this special relationship is that, with exceptions, children tend to live with their parents until at least the age of 18, giving parents a unique opportunity for influence.

This fact raises the question of whether, even if children have the capacity in the sense of having a general competence that underlies autonomous agency, they lack the specific ability to exercise it. Perhaps what really matters is not only that one is an autonomous agent, but that one has the opportunity to exercise one’s autonomy. In fact, returning to the comparison of the conditions for criminal liability, we see that in any given instance of criminal wrongdoing, we require both competence and that the situation allow for its exercise. The criminal law recognizes incompetence excuses (and the insanity defense is most often read in this way), but also situational excuses, such as duress. A person might be a highly competent and reasons-responsive adult, and yet find herself in circumstances that make it unreasonable to expect her to act well, such as when the life of a close family member or friend is threatened unless she commits a crime. Thus, what seems essential in the criminal context is that one have an opportunity of sufficiently high quality to avoid wrong-doing, where that is a function of both one’s competence and one’s situation. If we think of voting as also requiring a high quality opportunity to exercise one’s autonomy well, and parental influence as a situational factor appears to significantly compromise the quality of opportunity, then a voting age of 18 would seem warranted after all.

Although this is an important argument, I believe that both premises in this reasoning can be questioned. On the one hand, we can question whether the cases of criminal liability and eligibility for voting rights have asymmetrical requirements. Perhaps criminal liability requires opportunity to act in certain ways, which is only partly a function of competence, while voting rights only requires competence. Depending on the rationales one accepts for the importance of voting, one might give different answers. If voting were merely a symbolic marker of a status, as important as this is, it might be that only competence is needed. Whether one is in a position to exercise it well is less important in this case. But other rationales suggest that not only competence, but also opportunity, is essential. If one’s vote is to have a chance at succeeding in expressing one’s view of what the reasons support, for example, one must possess not only the relevant skills and talents, but also the opportunity to exercise them in given instances of voting. But rather than see these reasons as competing, I would rather accept both. This means that we either accept a factor in addition to capacity, namely situational congeniality, that allows for the opportunity to exercise the capacity in question, or we adopt a more expansive understanding of “capacity” on yet another dimension to encompass opportunity itself. Either way, we can accept the first premise in this reasoning.

We should instead focus our efforts on rejecting the second premise in the reasoning, namely, the claim that the parental influence compromises quality of opportunity to a sufficient degree. While this will largely be an empirical question to be settled by the empirical evidence, it is also important to note that the burden is lighter than it might initially seem. First, the burden is not to show that parental influence never compromises such opportunity to a sufficient degree. As we saw before, we can accept that we will pay a price of false positives in order to offset the risk of false negatives. Second, the burden is also comparative: if parental influence for 16- and 17-year-olds in the sphere of voting in particular is not more compromising than parental or other influence is for older age groups, this is also reason not to take parental influence as a reason to restrict the voting age to 18. Third, it turns out that evidence in favor of parental influence being sufficiently compromising is harder to come by than might be thought, as well. Showing mere similarity in political affiliation between children and parents will not suffice for showing that influence impairs opportunity, nor will showing causation of similarity in affiliation. What matters is whether opportunity has been compromised and this is not shown in either of these ways. For one might be influenced by one’s teachers not to bully fellow students, but this need not compromise one’s opportunity to exercise one’s autonomous choice not to bully. Responding to the teacher’s good reasons by adopting them as one’s own might be an ideal exercise of autonomous agency. Or one might accept the bad advice of one’s role model without lacking the opportunity to have avoided taking it. Thus, research purporting to show that children often adopt the political affiliation of their parents is not by itself sufficient to show lack of relevant opportunities to exercise autonomous agency.

While a complete weighing of burdens is not possible here, it is notable that some influential recent research raises serious questions even about the extent of direct transmission of political affiliation from parents to children, and some suggests that significant transmission of political engagement might go in the opposite direction. Further, studies like the ones with which we began which support the idea that younger voters vote in significantly different proportions on certain issues than older voters offer indirect evidence that high enough quality opportunities remain when it comes to at least some issues. Thus, while I do not here provide anything like a full reply to the objection from parental influence, I believe that there is at least good reason to resist it. If the empirical facts prove different from what they seem, then this argument would need to be revisited.

A second reason for doubting whether it is capacity that should underly an age requirement takes this same observation about the age of emancipation as a starting point, but develops it in a different way. Yaffe (2018) offers an argument from parental influence that begins with the observation that before the age of emancipation parents have rights to inculcate values in their children and to exercise a certain amount of control. But if that is the case, he argues, and children younger than 18 were to have the right to vote, then there is a way in which parents would have unequal input into the democratic process by in effect having more than one vote each. This seems problematic on grounds of equality. At the same time, he argues, it is legitimate to allow parents this influence over their children at least partly for the very reason that we think it is legitimate for them to have influence over not only the laws of today, but also the laws of tomorrow. The goal of balancing equality with allowing parents the ability to influence the future by influencing their children’s values is a compelling enough interest to deny the vote to those under the age of 18. As Yaffe writes:

Eighteen is an appealing threshold, I suggest, precisely because people of that age tend to be free enough from their parents to make their own decisions, albeit guided by values their parents might have inculcated, and, further, if they have not come to be guided by values their parents inculcated, they are not likely to do so ever.

Thus, according to Yaffe’s reasoning, the best way to achieve the dual goals of providing people a way of shaping future laws and respecting equality is to deny the vote to those under 18. But this is not because 18 is a proxy for an elusive capacity; it is rather because it is the age at which we are best able to balance and promote these two important goals.

As interesting as this suggestion is, we can resist it. First, as just discussed, it is an empirical question just how “free” from their parents—or anyone else—16- and 17-year-olds are to make their own decisions, and there is at least a fair amount of evidence that opposes Yaffe’s position on this point. Relatedly, once we recognize different domains of decision-making, as we do when it comes to peer pressure, the burden is even greater to show that parental control overwhelms opportunities of sufficient quality to vote freely. It is one thing for parents to control when a child returns home in the evening, and another to control how a child votes. Perhaps the control is just as great in many cases, but there is nothing obvious about that. And second, the assumption that there would be a certain violation of equality if children were to vote while being influenced by their parents is questionable. If in fact many 16- and 17-year-olds are autonomous agents with the capacity and opportunity to vote well, it is hard to see how their situation is relevantly different in any significant degree from 18-year-olds with similar capacities. The value of giving autonomous agents with a stake in their own future the right to vote is a significant one, and it is not dislodged by the fact that parents have influenced their children.

A third reason for thinking that there should be an age minimum that is not tied to capacity is that age marks instead a particular “stage of life”, as Franklin-Hall (2013) calls it. In defending the idea that paternalism of certain sorts (particularly in requiring certain sorts of education) can be justified for those under 18, Franklin-Hall notes that such state interference cannot be justified on the grounds that those under 18 are lacking in capacities thought to underly autonomy. Rather, he argues that infringements in their “local” or time-specific autonomy can be justified on grounds that by interfering at this early life stage their global autonomy, or ability to be authors of their own extended lives, will be enhanced. The idea here is that age marks a special life-stage, rather than a set of capacities, and that it is the life-stage that has special features that justify a kind of paternalism by the state. This is an intriguing argument. But a parallel justification of the same sort does not seem readily available in the case of voting. In the case of requiring those under 18 to receive an education, the justification is, at least in part, that it is enhancing of their own autonomy over the long run. But there is no obvious counterpart in the case of prohibiting younger teens from voting. Thus, while this alternative to capacities might very well suggest that other age requirements ought not to exclusively track capacities, it does not give us good reason to reject capacities as what matters most in voting.

8. Conclusion

In this paper, I have argued that the voting age should be lowered to 16 on the grounds that this age is a good proxy for what really matters, namely, an expansive capacity along two dimensions. The capacity is expansive in including both cognitive and volitional components, and in encompassing both competence and situational factors that provide an opportunity to exercise that competence. Despite the expansiveness along both of these dimensions, there is good reason to think that the empirical facts support the inclusion of 16- and 17-year-olds on the basis that they have the doubly expansive capacity in question. At the same time, I have noted that if empirical work develops in unanticipated ways the argument would need to be reworked. But this empirical dependence seems to me a strength, rather than a weakness, of the argument. At a number of points throughout the paper, I have turned to the debate about the age of criminal liability for comparison and support. Even where the parallels break down, each debate can inform the other in ways that have been well-documented, but also in ways that I hope to have shown have thus far been under-explored.

Acknowledgements: Many thanks to Tom Douglas, Guy Kahane, Sam Rickless and two anonymous referees for their very helpful comments on previous written versions, to Alice Rickless and Sophie Rickless for inspiring discussion, and to Gail Heyman for guidance in the psychological literature on peer pressure. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Kyoto University-UC San Diego Philosophy Workshop in January 2018, and I am grateful to the participants for their input. Finally, my ideas for this paper developed while teaching an undergraduate class, Law and Society, at UC San Diego, and I thank the students for stimulating discussions of this issue.

References

American Law Institute. (1981/2002). Model Penal Code, ed. M. Dubber, (New York: Foundation Press).

American Psychiatric Association. (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), Fifth Edition.

Appelbaum PS, Bonnie RJ, Karlawish JH. (2005). “The capacity to vote of persons with Alzheimer’s disease,” American Journal of Psychiatry 162: 2094–2100.

Bennett, Christopher. (2016). “Penal Disenfranchisement,” Criminal Law and Philosophy 10: 411–425.

Bratman, Michael. (2007). Structures of Agency: Essays (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Brennan, Jason and Hill, Lisa. (2014). Compulsory Voting: For and Against (New York: Cambridge University Press).

Brink, David O. (2004). “Immaturity, Normative Competence, and Juvenile Transfer: How (Not) to Punish Minors for Major Crimes.” Texas Law Review 82: 1555–85.

Brink, David O. and Nelkin, Dana Kay. (2013). “Fairness and the Architecture of Responsibility,” Oxford Studies in Agency and Responsibility 1: 284-313.

Buss, Sarah and Westlund, Andrea, “Personal Autonomy,” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), Accessed at https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2018/entries/personal-autonomy/ (accessed 19 August 2020).

Chan, Tak Wing and Clayton, Matthew. (2008). “Should the Voting Age be Lowered to Sixteen? Normative and Empirical Considerations,” Political Studies 54: 533–558.

Dahlgard, Jens Olav. (2018). “Trickle-Up Political Socialization: The Causal Effect on Turnout of Parenting a Newly Enfranchised Voter,” American Political Science Review 112: 698–705.

Diavalo, Lucy. (2019). “California Has Pre-registered More Than 400,000 16- and 17-Year-Old Voters in Three Years—Here’s How,” Teen Vogue. Accessed at https://www.teenvogue.com/story/california-pre-registered-400000-teen-voters-three-years-alex-padilla (accessed 19 August 2020).

Dressler, Joshua. (2018). Understanding the Criminal Law 8th edition (Carolina Academic Press).

Fischer, John Martin and Ravizza, Mark. (1998). Responsibility and Control: A Theory of Moral Responsibility (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Frankfurt, Harry. (1971). “Freedom of the Will and the Concept of a Person,” Journal of Philosophy 68: 5-20.

Franklin-Hall, Andrew. (2013) “On Becoming an Adult: Autonomy and the Moral Relevance of Life’s Stages,” The Philosophical Quarterly 63: 223-247.

Jaworska, Agnieszka. (1999). “Respecting the Margins of Agency: Alzheimer’s Patients and the Capacity to Value,” Philosophy and Public Affairs 28: 105–38.

Knutzen, Jonathan. (in preparation). A Reason-First Approach to Personal Autonomy.

Leber, Rebecca. (2016). “Younger Brits just had their future decided for them,” Grist (Jun 24, 2016) accessed at https://grist.org/article/younger-brits-just-had-their-future-decided-for-them/ (accessed 19 August 2020).

López, P., Valls, N., Verd, J. M., & Vidal, P. (2006) La realitat juvenil a Catalunya (Barcelona, Spain: Observatori Català de la Joventut, Secretaria General de Joventut, Generalitat de Catalunya).

López-Guerra, Claudio. (2012). “Enfranchising Minors and the Mentally Impaired,” Social Theory and Practice 38: 115-138.

Mill, John Stuart (1861/1975) Considerations of Representative Government in Three Essays, edited by Richard Wollheim (Oxford University Press).

Morse, Steven. (2002). “Uncontrollable Urges and Irrational People.” Virginia Law Review 88: 1025–78.

Munn, Nicholas (2012). “Reconciling the Criminal and Participatory Responsibilities of Youth,” Social Theory and Practice 38: 139-159.

Nelkin, Dana Kay (2011). Making Sense of Freedom and Responsibility (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Ojeda, Christopher and Hatemi, Peter K. (2015). “Accounting for the Child in the Transmission of Party Identification,” American Sociological Review 80: 1150–1174.

Peto, Tommy (2017). “Why the Voting Age Should Be Lowered to 16,” Politics, Philosophy, and Economics: 1-21. 17(3): 277-297.

Platt, Anthony and Diamond, Bernard L. (1966). “The Origins of the “Right and Wrong” Test of Criminal Responsibility and Its Subsequent Development in the United States: An Historical Survey,” California Law Review 54: 1227-1261.

Rico, Guillem and Jennings, Kent M. (2016). “The Formation of Left-Right Identification: Pathways and Correlates of Parental Influence,” Political Psychology 37: 237-252.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques (1762/2018) The Social Contract in The Social Contract and Other Later Political Writings, Second Edition, edited by Victor Gourevitch (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Ryazanov, Arseny, Knutzen, Jonathan, Rickless, Samuel C., Christenfeld, Nicholas, and Nelkin, Dana Kay. (2018). “Intuitive Probabilities and the Limitation of Moral Imagination,” Cognitive Science 42: 38-68.

Sim, Tick Ngee and Koh, Sui Fen. (2003). “A Domain Conceptualization of Adolescent Susceptibility to Peer Pressure,” Journal of Research on Adolescence 13: 57-80.

Steinberg, Laurence, Cauffman, Elizabeth, Woolard, Jennifer, Graham, Sandra and Banich, Maria. (2009). “Are adolescents less mature than adults? Minors’ access to abortion, the juvenile death penalty, and the alleged APA ‘flip-flop’,” The American Psychologist 64: 583–594.

Steinberg, Laurence and Monahan, Kathryn C. (2007). “Age differences in resistance to peer influence,” Developmental Psychology 43: 1531-1543.

Vargas, Manuel. (2013). Building Better Beings (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Wagner, Markus and Zeglovits, Eva. (2014). “The Austrian experience shows that there is little risk and much to gain from giving 16-year-olds the vote”. In Berry R and Kippin S (eds) Should the UK Lower the Voting Age to 16? (London: Democratic Audit). 19–20.

Waldron, Jeremy. (1993). “A Right-Based Critique of Constitutional Rights,” Oxford Journal of Legal Studies 13: 18-51.

Watson, Gary. (1975). “Free Agency,” Journal of Philosophy 72: 205-220.

Wolf, Susan. (1990). Freedom Within Reason (New York: Oxford University Press).

Yaffe, Gideon. (2018). The Age of Culpability: Children and the Nature of Criminal Responsibility (Oxford: Oxford University Press).